Arrested years ago for marijuana, Christopher M. McClinton sleeps in an Alabama prison at night. He spends his days working at a fast food restaurant, slinging fries and milkshakes in a small town near the Gulf.

The state keeps about 40% of each of his paychecks. And the state will not grant him parole.

“I don’t know what they want him to do,” said his mother, Willamener Gales.

Gales, along with McClinton’s pastor, spoke on her 38-year-old son’s behalf at his parole hearing last August. He has a job, she said. He could live at her house, she said.

But the odds of getting a second chance are low in Alabama, and McClinton’s odds are worse than many others. Alabama’s parole board denies Black men at a higher rate than any other group.

Gales only had two minutes to speak in front of the board last August - hardly enough time to tell them that her son was remorseful, that he needed to be home for his children, or that he had previously been allowed passes from prison to stay at her house on some weekends.

“Their mind was made up before I went before them,” she told AL.com.

McClinton, like Bud Hotchkiss, is serving time at the Loxley work release center for marijuana. He had just enough — over 2.2 pounds — for the state to charge him with trafficking.

He pleaded guilty in 2010 and was sentenced to 20 years and a $25,000 fine. He was ordered to spend the first three years in prison, getting released on probation in 2013.

McClinton was still on probation when, in 2016, police caught him with a small amount of codeine and charged him with possession of a controlled substance. He had missed a few drug tests in those three years and tested positive for drugs once, according to court records. So, a judge revoked McClinton’s probation, sending him back to prison to serve out the remaining 17 years on his marijuana sentence.

He also pleaded guilty to the codeine possession, and he got 10 years to serve at the same time on that charge.

Yet the state says, like the other thousands of low-risk prisoners in Alabama, he’s fine to work in public most days.

At the parole board last summer, Gales spoke first.

She said that McClinton has worked at a fast-food restaurant in Foley for the past two years and his bosses have said they would let him keep his job if paroled. And, he would go home to live with his mom.

Gales told them her son had learned his lesson, that while he put himself in prison in the first place, he’s remorseful and has been behind bars long enough to have been rehabilitated.

A sweeping lawsuit filed by prisoners and labor unions last month accuses Alabama of running a “labor-trafficking scheme” that generates millions of dollars each year for the state. More than 500 companies have contracts with the Alabama Department of Corrections to obtain work from inmates, the complaint said.

“Labor coerced from Alabama’s disproportionately Black incarcerated population is the fuel that fires ADOC’s extremely lucrative profit-making engine,” the lawsuit reads. McClinton isn’t a plaintiff in that lawsuit.

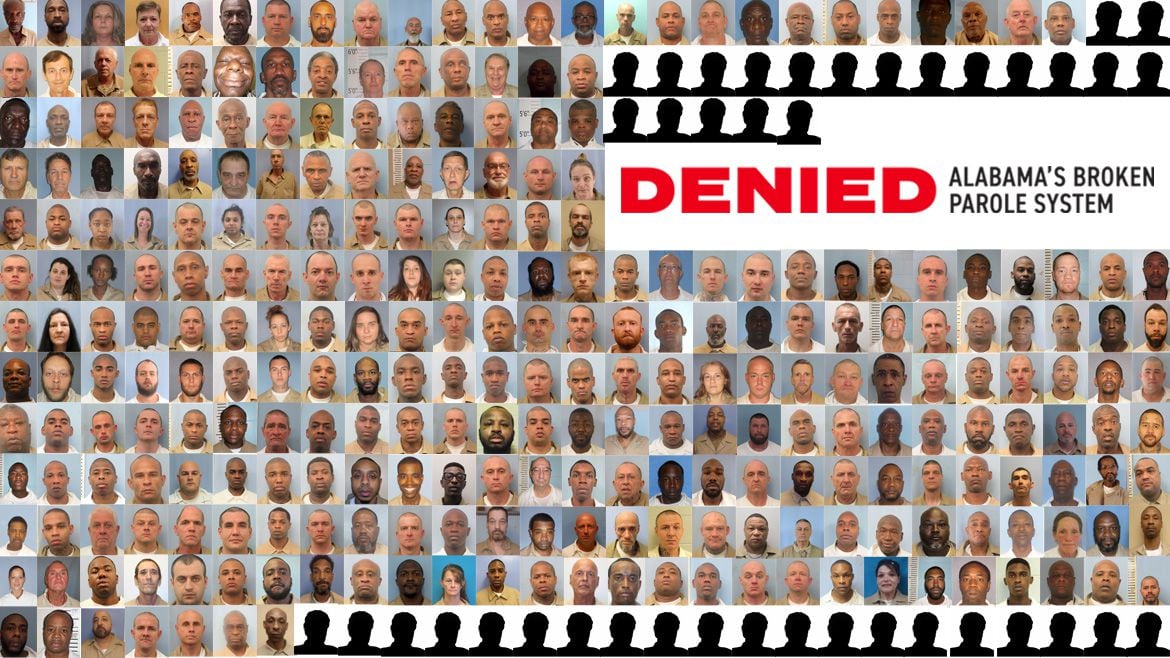

Last year AL.com found Black men were being paroled less often and serving more of their sentences than white men.

AL.com was able to gather detailed demographic information and case histories for 640 of the 662 people that came up for parole during a two-month window in April and May last year. Most of the people who got parole were white, despite most coming before the board being Black.

In the end, Black men were about 25% less likely to be paroled than white men during those two months.

However, just five years ago, most people in Alabama were granted parole. That’s now down to 8%.

In front of the parole board, McClinton’s pastor talked about taking the young man under his wing, mentoring him when he was able to come home on passes from the prison.

Then a representative from the Alabama Attorney General’s Office spoke about the 10 infractions McClinton had in prison. There is no chance for rebuttal. Hearings only last minutes, which each speaker getting just 120 seconds. Gales wasn’t able to explain that almost all of those infractions were from nearly a decade ago. None were for violent offenses; the latest was for drinking.

“He was angry at that time. I’m not making excuses for him,” she said. “But things have changed.”

The board voted to deny his parole. McClinton won’t get another shot at freedom until August 2025; he’s already served more than a decade behind bars on his drug offenses.

Gales said her son didn’t understand why people who are charged with crimes that left someone hurt or even killed could spend less time in prison than he has for having a few pounds of pot, even though she made it clear she didn’t condone her son’s actions.

As for the parole board, she said: “I feel they’re prejudiced.”

Denied: Alabama's broken parole system

- Alabama lawmakers distance themselves from parole board, families say loved ones ‘stuck for life’

- Alabama argued to keep Lowe’s shoplifter in prison. Roy Moore came to his defense.

- Alabama paroles hit historic lows last year: Here’s what changed amid scrutiny in 2024

- He missed a meeting and got sent back to prison. Now Alabama is giving him another chance.

- They want to ‘die with a clear conscience.’ But in Alabama, pardons are harder to come by

This project was completed with the support of a grant from Columbia University’s Ira A. Lipman Center for Journalism and Civil and Human Rights in conjunction with Arnold Ventures.