Kenny McCroskey didn’t commit a crime. Not the last time he was sent back to prison. But he did miss an appointment.

“I feel like I deserve to be punished,” McCroskey said quietly from a prison phone. “But I deserve an opportunity.”

His case represents yet another challenging part of Alabama’s unforgiving parole system: The parole board these days is not only denying nearly everyone who tries to get out of prison, they are also sending people back to prison who were already let out, even when they haven’t committed any new crimes.

And in McCroskey’s case, that’s despite the lenient recommendation of the parole officer whom he failed to meet with.

Now, McCroskey is once again behind bars, serving a life sentence for violating the rules of his parole for a third-degree robbery in 1996.

He was unarmed, though he told the cashier he had a gun, and demanded money from a Hardee’s. No one was hurt. He didn’t get any money. But he’d had two earlier convictions, so he was sent to spend his life in prison.

He was sentenced under the state’s outdated Habitual Felony Offender Act laws, laws that the state has since changed. But that change didn’t affect McCroskey or anyone long ago sentenced on the old, “three strikes, you’re out” rule.

Now 55, he laughed when asked if the unarmed, unsuccessful robberies he committed in north Alabama in the early 1990s were because he was young and dumb. He said it might be a little harsh of a description, but it was true.

“You may think it’s crazy, but you really have to be in the lifestyle I was in,” McCroskey said in a phone interview, describing being immersed in alcohol and drugs while in his 20′s. “The robbery came into play behind the lifestyle. It’s hard talking to a person who has never been through it.”

After a decade behind bars for the failed attempt at Hardee’s, in 2006, he was granted parole.

McCroskey said he again got “caught up” with the wrong people. “I made wrong choices.”

Shortly after being released, he tried to rob another fast food restaurant. This time it was a Jack’s, where court records say he reached over the counter, trying to take the cash register.

Again, he didn’t have a weapon. And, again, he didn’t get any money. Once again no one was hurt — except McCroskey himself. He was tackled to the ground by an off-duty deputy and had to have stitches, court records show.

That time McCroskey was sentenced to spend 17 years in prison on a new charge of third-degree robbery.

And that’s when, McCroskey said, he finally got his act together.

It paid off.

Alabama just a few years ago was granting parole to more than half of those who came up for release, and McCroskey got another chance. He was paroled in 2015.

He got a good job, working at Polaris in Madison. He was able to spend time with his family. He was doing so well on parole, McCroskey said, his parole officer explained to him how to apply for a pardon once he paid off his court fines and fees.

“I can’t be that bad of a person if someone looked at it in that light,” he said. “But of course” he sighed, “I messed that up when I didn’t report.”

In 2019, after years outside prison walls, McCroskey went to a funeral. But the funeral was on the same day he was set to appear at his parole office.

“It was a poor decision, and I can’t blame it on anyone but myself,” McCroskey said.

Not reporting is a technical violation. He had to go before the state parole board to let them hear the situation and decide how he should be punished. But by 2019, things had changed. Alabama’s board was different. They were no longer granting many paroles and were under new leadership, taking a hard stance on technical violations.

Most minor parole violations, like missed meetings, are handled by what are called “dips” or “dunks” — short periods of time ordered in local jails or other lockups — before letting the parolee back on the streets with a warning.

His parole officer recommended a dunk, which would have been 45 days behind bars. Instead, the board sent McCroskey back to Alabama’s overcrowded and understaffed prisons indefinitely.

In October 2023, according to data from the parole bureau, 20 people had their parole revoked for technical offenses.

For those who had a revocation hearing for an alleged parole violation in fiscal year 2023, 16 percent were revoked on a technical violation alone, according to bureau data. That means they had no new criminal charges, but were returned to prison.

McCroskey has now served a total of more than 27 years behind bars, all for offenses where no one was hurt. The last criminal charge he faced was for the Jack’s attempt in 2006 — 18 years ago.

He’s served all his time on that one, his most recent charge. So why isn’t he free?

It goes back to 1996.

That was when he pleaded guilty to a life sentence under the habitual offender law. If he was ever freed, he would forever be on parole, tethered to that older charge and liable to pay for it anytime he re-entered the corrections system.

He’s been back in prison now for almost five years. He spent time at Alex City’s work release center, but was moved after he was caught drinking (a stupid decision, McCroskey said). He had a good prison record, though, and wasn’t deemed a risk. So he was moved to a different work release center with minimum security in Childersburg.

McCroskey went up for parole last May, but was denied. He’s set to go back before the board in May 2024.

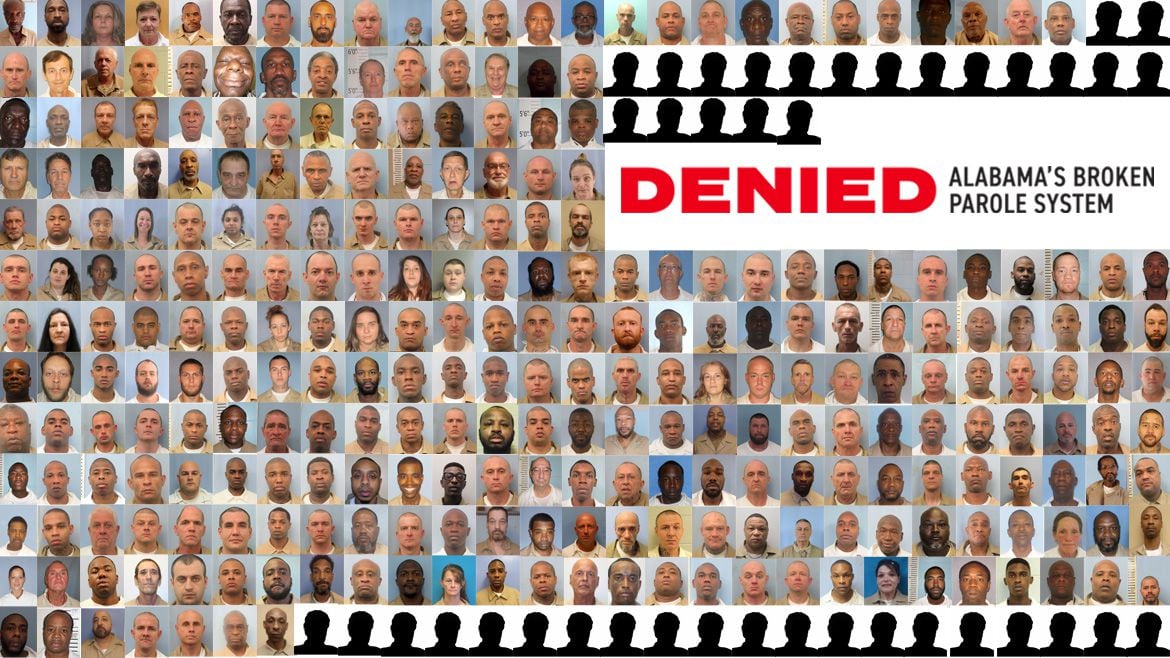

Denied: Alabama's broken parole system

- Alabama lawmakers distance themselves from parole board, families say loved ones ‘stuck for life’

- Alabama argued to keep Lowe’s shoplifter in prison. Roy Moore came to his defense.

- Alabama paroles hit historic lows last year: Here’s what changed amid scrutiny in 2024

- He missed a meeting and got sent back to prison. Now Alabama is giving him another chance.

- They want to ‘die with a clear conscience.’ But in Alabama, pardons are harder to come by

If he is freed, McCroskey said he wants to work at a job he’s lined up in Guntersville. He’s got financial support and a place to live, and is yearning for a cup of non-prison coffee.

McCroskey wants to be there for his son, two granddaughters and extended family, “to live the remainder of my life that’s left on the outside.”

He lived crime-free for years when he was last paroled and hasn’t been charged with a crime in nearly two decades. He says he wants another chance to show he can do it again.

“That’s what it’s going to take first. It starts with me.”

This project was completed with the support of a grant from Columbia University’s Ira A. Lipman Center for Journalism and Civil and Human Rights in conjunction with Arnold Ventures.