Alvin Freeman says he’s turned his life over to God in the 42 years since he was a getaway driver.

Now a 79-year-old grandfather, dependent on an oxygen tank, he says that robbery conviction, the one that sent him to prison for seven years, continued to haunt him for decades after he got out. The lasting parole prevented him from traveling out of state to visit his grandchildren.

“Freedom means everything,” Freeman told AL.com. “People don’t realize what freedom does mean until you don’t got it no more.”

Alabama isn’t as stingy with pardons as with paroles. But the same three-member board handles both, and the forgiveness of long ago crimes and restoration of rights has also become harder to come by in recent years. That’s the right to vote, the right to own a gun, and for some, the ability to leave the state.

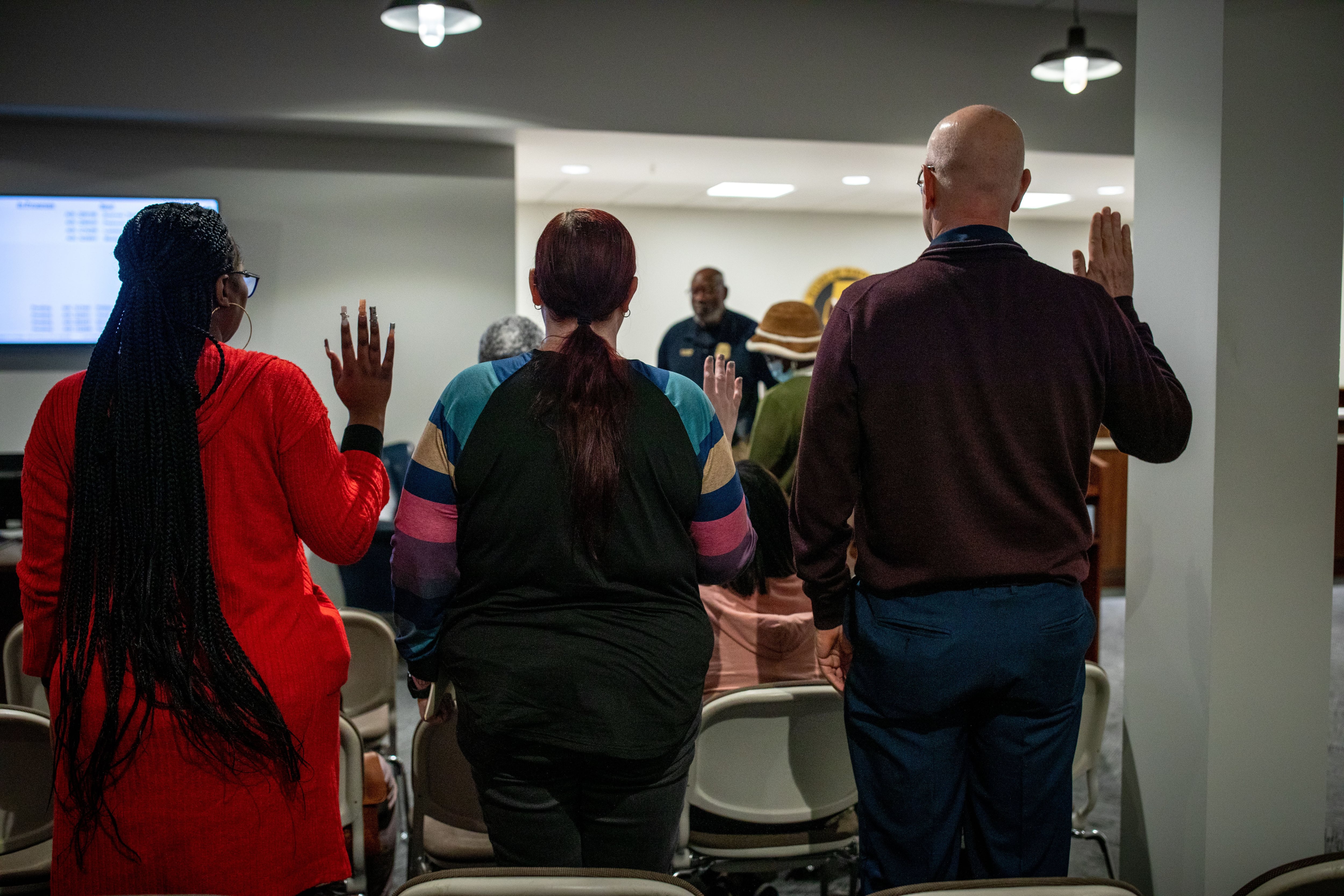

Standing before the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles, Freeman said that he has remorse and was “very young and very wild” at the time of his crimes. But he’s been sober for 34 years and became a productive citizen who “recommitted to Christ.”

Matt Merill, the executive director of the ARC re-entry program in Bessemer, attended the hearing with Freeman as his advocate. He said a pardon can change a younger person’s life, give them new opportunities.

“But I would say most of the older individuals that have been in trouble, they just need that for themselves,” he said. “That’s why I don’t understand why pardons are so hard to grant because they really just want to die with a clear conscience.”

Asking for forgiveness

Stanley Anderson wanted a pardon so he could coach his kids’ little league teams, something people with felony convictions are not allowed to do.

Carla Cruise asked for a pardon so she could visit her son on a military base and become a licensed home builder in Alabama. She got her welding certificates in prison and now employs people who also need a second chance.

Anthony Buskey wanted one so he could go to jobs on military bases for the asphalt and construction company where he works.

Demarcus Knight wanted a pardon so he could get into nursing school and continue toward his goal of working in a nursing home.

Nadja Hamilton sought a pardon so she can become a US citizen, something she can’t do with a criminal record even though she’s married to an American.

William Rowe said he served in the army and “was a good soldier.” He asked for a pardon so he can take his grandkids hunting and get his voting rights restored.

Each time the board voted to grant a pardon, the quiet room erupted in celebration. Many applicants cried. One couple kissed. “I never thought I’d see that in a hearing,” remarked Leigh Gwathney, the chair of the pardons board.

On March 7, the day Freeman first asked the board to grant him a pardon, he watched 10 other applicants go before him. But he and four others left that day without a pardon because of a tie vote.

He’d have to try again on April 11.

A different board

Freeman’s not able to do much work with his health conditions, but he used to help repair cars and lawn mowers in Prattville.

“I’ve been out 30 years and I’ve been true,” Freeman told the board on March 7. “If I can get a pardon I’d like to spend a little time with the rest of my family and get away from being tied down here…I have tried my best to keep up my end of the parole you have given me and I believe now I am ready for a pardon.”

But the board split over Freeman’s request.

In 2019, Gwathney became the chair of the board. Since then, both pardons and paroles have gone down. Under her leadership, the board went from granting 53% of paroles in 2018 to only 8% in 2023.

Meanwhile, the same board granted 55% of pardons last year. But that’s also a big drop, down from 80% in 2018 before Gwathney took over.

Gwathney did not respond to an emailed list of questions for this article.

Split vote

Pardons can restore voting rights and gun rights, and in some cases free people from strict parole requirements and provide access to better job opportunities. It does not, however, expunge your record.

And while the grant rate remains higher for pardons than paroles, experts note that the risks are also much lower.

“With pardons you’ve already done your crime and you’ve already completed your sentence,” Cam Ward, the director of the Bureau of Pardons and Paroles, told AL.com. “That’s just giving someone their rights back — that’s why with pardons you’ll always have a higher grant right, I’m assuming, than you will with paroles. It would be an easier vote for them to make.”

AL.com attended hearings during a two-week period when 173 people were scheduled for pardon or parole hearings. But the board only voted in public in 101 of those cases.

Gwathney told AL.com that it has always been standard protocol that when no one is present to speak on an applicant’s behalf, those votes are held in executive session.

Of the 44 pardon hearings AL.com observed, the board denied eight applicants, granted 31 pardons and had a tie vote in five hearings, meaning the board could not come to a decision and would vote on the case again in a month.

The day Freeman first asked for his pardon, Gwathney sat at the dais with associate member Daryl Littleton. Gwathney and Littleton often diverge. Of the 44 pardons cases observed by AL.com this year, Gwathney voted no on 25%. Littleton voted no just 9% of the time.

But Gabrelle Simmons, the third member who often casts the deciding vote, was out sick that day.

Gregory Hollis wanted a pardon for receiving stolen property in 1997 — he said he “bought something from a friend not knowing it was stolen and took it to the pawn shop” — and a 2002 burglary conviction. In the burglary case, Hollis broke into his neighbor’s apartment. He didn’t take anything or injure anyone. Instead, he ended up getting shot by someone else in the neighborhood.

Like Freeman, Hollis got a split vote on March 7.

When Hollis returned a month later for a new hearing in front of the full board, Littleton and Gwathney’s differences were clear in their questions. Gwathney wanted to talk about the crimes from more than two decades earlier. Littleton, a former state trooper, asked about Hollis’ addiction and his recovery in the years since he left prison.

Unlike at parole hearings in Alabama, those seeking pardons are allowed to speak on their own behalf.

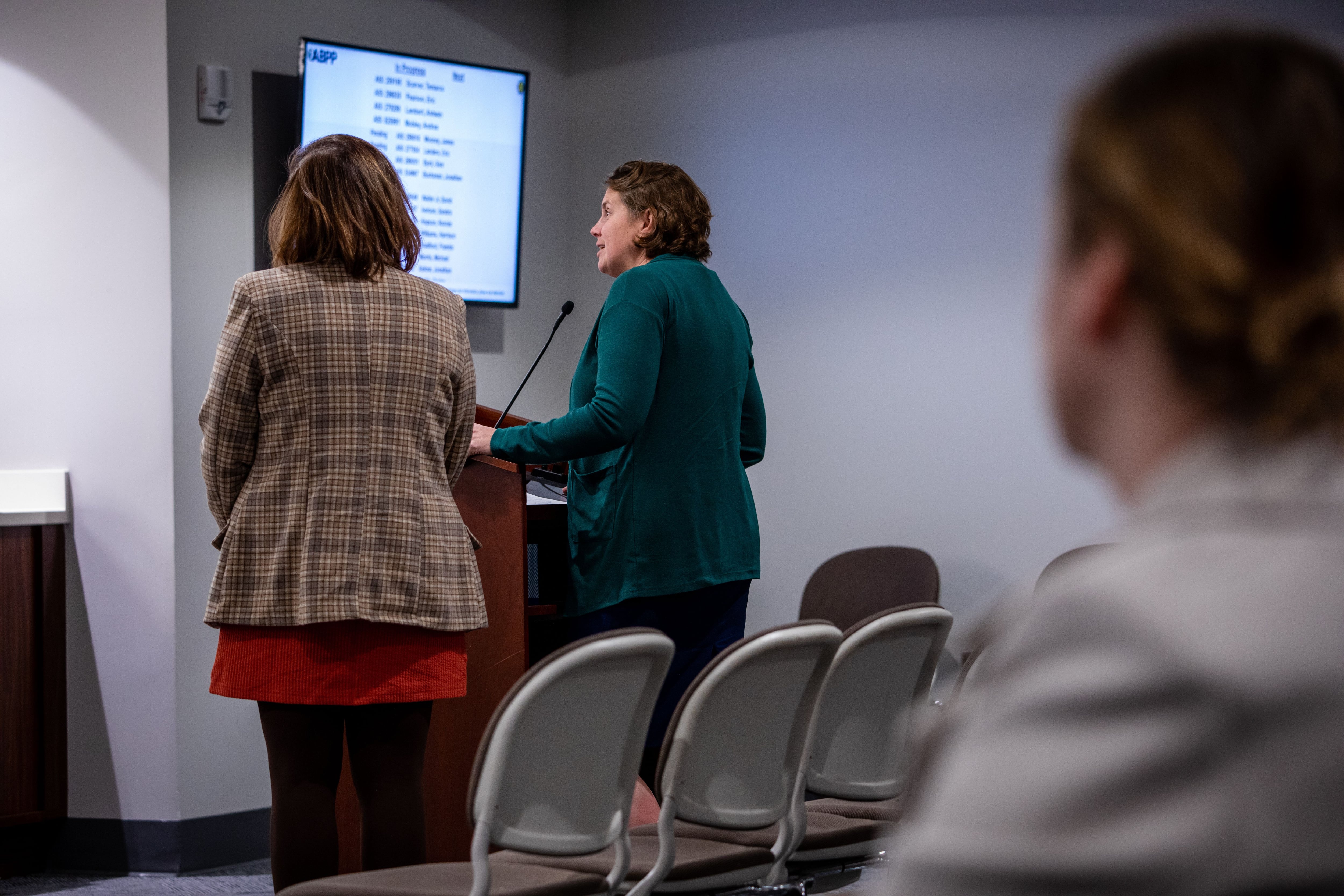

Rhonda Carter, the hearings coordinator for the Bureau of Pardons and Paroles, offers advice to applicants in the waiting room: “I’m going to be completely transparent with you…the board is only looking for your actions that day. They’re looking for complete transparency, accountability and remorse.”

Attorney General Steve Marshall’s Office frequently speaks against pardons. So does the advocacy group, Victims of Crime and Leniency, or VOCAL, when a violent crime has been committed.

The Attorney General’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

“Mr. Hollis, you said you threw a flower pot through the door and that you remember being shot. What happened in between throwing the flower pots and getting shot?” Gwathney asked.

Hollis responded that he could barely remember that day decades ago, but can recall “someone hollering at me and hollering at me to freeze and there was all kinds of commotion going on so I ran through the front door.”

Gwathney, a former prosecutor in the attorney general’s office, continued to ask what he remembered — what door he exited out of, what he was carrying in his hands. She wanted to know what kind of ground he laid on when he left and why he laid in the woods after getting shot instead of going home to his apartment.

“I got shot,” Hollis responded. “I was hurting. It was real hard for me to move.”

Hollis told the board he’s a different person now — an ordained pastor, a man who ministers in his community, a husband, a tour bus driver who shuttles visitors to Alabama’s civil rights venues. He said that when he broke into his neighbor’s apartment he was high on pain medicine he’d been prescribed after a bad car accident and reconstructive surgery.

“Reverend Hollis, you’ve had medical difficulties and were under the influence of something we now know is a highly addictive and destructive opiate. Have you stopped using it and has your life changed since you stopped using?” Littleton asked.

“I would not even take a narcotic now if my doctor prescribed it,” he replied.

“Your company is insured and allows you to operate their $600,000 asset with 56 passengers…so they are fairly confident you do not have an opioid addiction at this time and I can assume we are not in the same place where you were a burglar, that you are now a different person?” Littleton then asked.

“Yes sir,” Hollis replied.

Denied: Alabama's broken parole system

- Alabama lawmakers distance themselves from parole board, families say loved ones ‘stuck for life’

- Alabama argued to keep Lowe’s shoplifter in prison. Roy Moore came to his defense.

- Alabama paroles hit historic lows last year: Here’s what changed amid scrutiny in 2024

- He missed a meeting and got sent back to prison. Now Alabama is giving him another chance.

- Battered woman shot her abuser 32 years ago. Alabama’s parole board won’t let her out.

Hollis, who is on parole until 2031, added that “I just want a pardon so I can get my rights back and have a new lease on life.”

Hollis’ wife said they wanted the opportunity to go on a honeymoon and on vacations together. “We just ask he’s granted the opportunity to enjoy family time together,” she told the board.

It didn’t matter. Gwathney and Simmons voted to deny. It was 2-1. Hollis did not get a pardon.

“You can come back and reapply in two years,” Gwathney told Hollis.

‘Having a voice matters’

At 30 years old, Micah Baker will vote for the first time this year after the board granted him a partial pardon for a 2014 marijuana distribution charge.

“You know, I haven’t been able to vote since I was able to vote because of my decisions that I made,” Baker told AL.com. “But now that I can vote, I will and I’m very excited.”

After someone is convicted of certain crimes, known as “moral turpitude” offenses in Alabama, they lose their right to vote and their right to own guns.

Alabama has the second highest disenfranchisement rate in the country at 9%, behind only Mississippi and tied with Tennessee, according to the Sentencing Project.

“Alabama is one of the remaining states that do not automatically restore voting rights after completion of sentence (in contrast to Georgia, Texas, and Louisiana),” said Chris Uggen, a professor at the University of Minnesota and author of the Sentencing Project’s report on felony disenfranchisement, in an email to AL.com. “This means that many people who were convicted and completed their sentences decades ago are still likely to be disenfranchised.”

But there are a couple ways to regain the right to vote.

People convicted of certain moral turpitude felonies — including child abuse, assault, manslaughter, burglary — can get their voting rights restored after completing their sentence if they don’t have any pending felony convictions, have paid all court debts, and have completed probation and parole. Then they can fill out a Certificate of Eligibility to Register to Vote without asking for a pardon.

Data from the Bureau of Pardons and Paroles shows that since 2020, those certificates have been granted at an average rate of 69%.

In cases where those criteria aren’t met, or if the person was convicted of an offense that Ward calls a ‘super bad’ crime, they need a pardon. Those 15 crimes include murder, rape, sodomy and sexual torture.

However, it’s not all about voting rights.

According to Ward, most of the time, people are applying for pardons to get their gun rights back. He said the board has some discretion on whether to grant gun rights, but with moral turpitude crimes, it is unlikely.

“For example, domestic violence, you’re likely not going to be granted, and this is an area of discretion for them,” Ward said. “But on guns, they’re pretty sensitive if you’ve committed a violent crime. If you were a murderer, you’re not going to get your gun rights back.”

While Baker got his voting rights back, the board declined to restore his gun rights, although his crime is not among those listed in the moral turpitude law. He said he plans to return in two years to ask again for the right to own a gun.

Rodreshia Russaw is the executive director of The Ordinary Peoples Society, which helps formerly incarcerated people get their rights back. She said there has been an uptick in people wanting help getting their gun rights back since Alabama passed its permitless carry law in 2022.

“There’s more harm right now if you’re not allowing for full pardons to happen. You’re talking about life or death because you have folks that are out here, unfortunately, using the fact that they don’t have to have gun licenses and just killing folks,” said Russaw, talking about the need for self defense. “People that have felony convictions, they have already been in cages. So they’re thinking to themselves, no, we’re not going to come unprotected, especially when you’re talking about mothers.”

According to bureau data from 2023, about 240 pardon applicants did not receive their gun rights back out of 855 granted applications.

‘Opens a lot of doors’

Alvin Freeman is not concerned with guns or voting as much as he is with freedom of movement.

Freeman wanted a pardon for that 1982 armed robbery case. He did not get out of the car and didn’t have a weapon. But he was the getaway driver. When the cops chased after them, he pulled over.

But the conviction was his third charge — he had a robbery conviction in Illinois and an intent to distribute charge from the 1970s — meaning under Alabama’s Habitual Offender Act, Freeman would remain on parole for life after prison. He couldn’t leave the state without permission and still had to attend regular check-ins with a parole officer, or face going back to prison.

During his seven years in prison, Freeman only had one disciplinary infraction, for being in an unauthorized area. He was the warden’s runner — essentially a personal assistant who has the freedom to move around the prison to run errands.

When Freeman got out on parole in 1989, the warden even wrote a letter to the board, praising Freeman for saving a baby from a hot car in the parking lot.

He hasn’t been in trouble with the law since he left prison.

When he went before the board seeking a pardon on March 7, Gwathney asked him to walk through each crime in detail.

“Sorry…It’s been 51 years, so it’s pretty hard for me to put it all together,” Freeman replied.

Gwathney and Littleton split that day. Freeman cried.

“What did I do wrong?” he asked later outside the hearing room.

When Freeman returned to the board a month later, the attorney general’s office protested his pardon.

“This is a habitual offender, violent crimes, robberies, and for that reason we are asking that it be fully denied,” said Sarah Deneve, a representative from the Attorney General’s office.

Kim Seago, Freeman’s roommate and caregiver, simply asked the board to “please let this Christian man die free.”

Gwathney voted against. But Simmons sided with Littleton. 2-1. Pardon granted.

Freeman lifted his arms in celebration at the decision as Seago cried and Merrill, his advocate, bowed his head in prayer. ”Thank you, thank you, thank you…” Freeman repeated.

Freeman doesn’t know how many years he has left. But he said he’ll spend the time he has with the people he loves.

“I’ve got grandchildren all over that I’ve never seen that I can visit. This just opens a lot of doors,” he said. “I’ve got to get well too. But I’ll get well now that I’m free.”