Thomas Owens can’t move his arms or his legs, so his likelihood of committing another property crime is low.

Yet, one member of the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles still voted last fall that the 34-year-old quadriplegic man should remain in prison. Board Chair Leigh Gwathney alone voted not to parole Owens to a long-term healthcare facility.

But Owens need not take it personally. Gwathney votes against nearly everyone whose case comes before the all-powerful parole board, a board that today serves as the cap on the shaken-up bottle that is the state’s troubled, jampacked prison system.

“I am convinced that the public should know that the chairman of the parole board voted to deny the medical parole of a nonviolent offender who is a quadriplegic, completely bedridden, and spends most of the day in a catatonic state,” said Sue Bell Cobb, whose legal foundation represents Owens.

“I don’t know how she sleeps at night,” said Cobb, the former Alabama Supreme Court Chief Justice who today runs a nonprofit that focuses on parole for prisoners with medical conditions. Alabama doesn’t grant many of those either.

And yet, Owens squeaked by. On a 2-1 vote, Owens, who was serving 12 years after pleading guilty to burglary, ID theft and receiving stolen property, was granted medical parole.

He became the rare exception for a board that last year granted just 8% of paroles. According to the board’s data, in fiscal year 2023, there were 3,583 parole hearings. Just 297 were granted.

That’s despite the parole board’s own guidelines suggesting more than 80% of the prisoners should qualify for a second chance. The board even rejected all 10 people over 80 who were up for parole in 2023.

It wasn’t always this way.

Just five years ago, more than half of those who had a parole hearing were granted release. But things changed in 2019 when Gwathney took over.

At the same time paroles began to slow to a trickle, the entire prison system ran into a crisis. The U.S. Department of Justice sued in 2020, arguing that Alabama prisons were overcrowded and understaffed, leading to so much death and violence and rape, that they failed to meet constitutional safeguards against cruel and unusual punishment.

They also argued the state wasn’t making it better and that the prisons were only growing more crowded. At the end of last year, according to state corrections reports, there were about 20,000 inmates packed into spaces built for just 12,000.

In 2021, the feds updated the suit, saying that the murder rate in Alabama prisons soared past the national average, that the buildings were crumbling, that there weren’t nearly enough guards, that rapes and extortion were rampant and that Alabama appeared uncooperative.

“The United States has determined that constitutional compliance cannot be secured by voluntary means,” wrote the Justice Department. The case is speeding toward a high-stakes trial scheduled for this fall.

So how did a troubled state penal system, one short on beds and guards, decide the best way forward was to keep the most people behind bars for as long as possible?

All signs point toward the parole board, said Rep. Chris England, D-Tuscaloosa.

“The buck stops there,” he said. “You don’t have to look very deeply into the process to say you guys, the chair… you are creating this disparity. Also, you are the problem. There’s really no other way to look at it.”

A couple of minutes

Owens’ hearing was postponed. It was originally set for the spring, but after his standard interview with a parole officer, the board canceled his hearing, saying he was uncooperative.

But he wasn’t unwilling to tell the board about his home plan, said Cobb. Not only can’t he walk, he also can’t speak.

Redemption Earned, the nonprofit legal group where Cobb serves as executive director, called the legal team for the parole board and explained the situation, and they responded they would look into the matter.

Eventually, Owens’ hearing was set for the fall. Gwathney still voted against him.

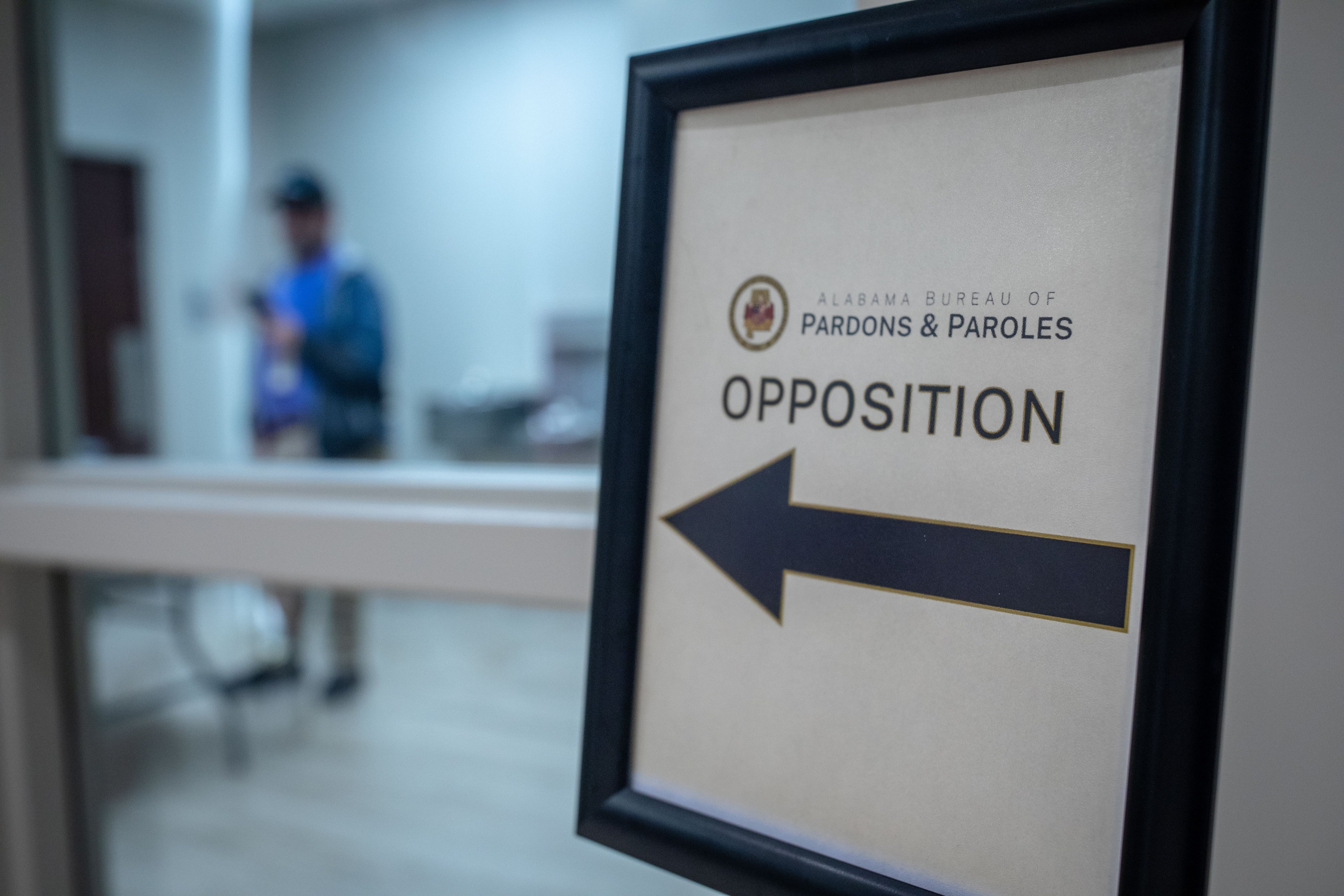

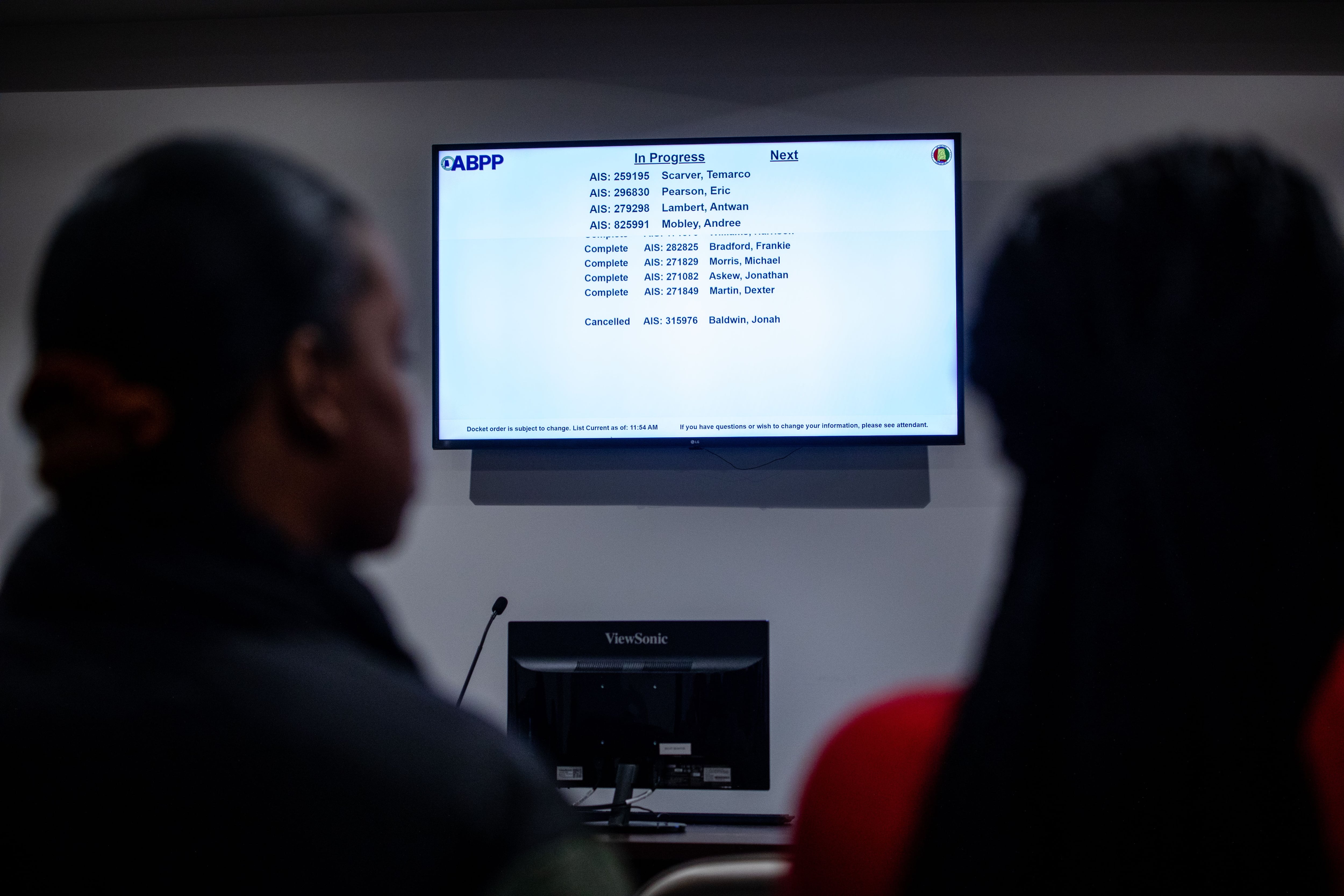

The state’s three-member parole board meets three days a week, listening to inmates’ advocates and victims alike, deciding who should have a second shot at living in the free world.

In Alabama, unlike in some other states, there’s no assumption that someone gets parole; it’s considered a privilege.

The hearings are open to the public. And while pivotal, the hearings aren’t cinematic. Inmates don’t get to attend, and often there are no advocates to speak for either side.

Each hearing lasts just minutes. If someone does speak, a small timer sits on the podium, ticking down the two minutes allotted for family or friends to make their case. The state or a victims advocacy group usually speaks in opposition when someone supports release.

Then, it’s up to those three people to decide whether to free someone, send a person back to prison for up to five more years before they can try again, or maybe make them finish their full sentence.

After listening to a handful of cases, it’s quiet. In a flash, the board decides.

Women get paroled more often than men, and white men fare better than Black men.

Black men were 25% less likely to get parole than white men, according to an AL.com analysis of data from a two-month window in April and May of 2023.

Non-violent drug offenders had a better chance to get out than someone convicted of what the state classifies as a violent offense. But after matching hearing results with individual records, few hard and fast patterns emerged regarding the original crime.

And no group does exceptionally well.

All sorts of people are denied. Many were caught with small amounts of drugs. Some are being held under old habitual offender rules that Alabama doesn’t have anymore. Some were once out on parole, got sent back on a technical violation like a missed meeting, and now find themselves stuck behind bars, unable to get out again years later.

In 2024, the decisions are made by chairperson Gwathney, former state trooper Darryl Littleton, and former Bureau of Pardons and Paroles worker Gabrelle Simmons.

A majority vote wins. And that’s hard to come by.

“Someone needs to ask Chairman Gwathney does she truly believe in parole,” said Cobb. “Because her voting record indicates that she does not.”

When AL.com approached Gwathney during the meeting on Jan. 9, she declined to comment. She said she had a meeting to run to. She also denied a formal interview request sent via email.

“If you commit technically a violent offense, regardless of the crime, regardless of the rehabilitations, regardless how many decades you spent behind bars, regardless how phenomenally well behaved you’ve been behind bars,” said Cobb, “she continues to vote no.”

“Apathetic attitude toward truth”

Before Gwathney led the board, there was Lyn Head.

Head, a prosecutor for nearly two decades, joined the board in 2016 and became chairperson in 2018. In the months before Head got to the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles, the number of people being paroled was rising.

It wasn’t because the board suddenly had a soft-on-crime approach. After dealing with an earlier threat of federal intervention into overcrowded and unsafe prisons, the state passed criminal justice reforms in 2015 that required board members to consider parole guidelines and criteria and consult those before making a decision.

The tool used at the time was the Ohio Risk Assessment. As a prosecutor, Head didn’t find it easy to vote to release someone with a serious charge, she said. But she dug into the national best practices for paroles, researching and attending various training sessions.

“That training opened my brain and I discovered that there’s science applicable to this. And that was the greatest discovery for me,” she said of relying on the risk assessment. “To have a concrete, scientific basis for granting or denying parole… it wasn’t a crystal ball, but it was the closest thing we had.”

In 2020, not long after Gwathney joined the board, the board adopted a new set of guidelines unique to Alabama.

But, the board isn’t using those, either.

Every month in 2023, according to data, the board’s own criteria indicated a recommended parole rate of about 80%. But they never came close to conforming to those guidelines. At the end of the year, they had met their own guidelines about 12% of the time.

“It’s really arrogance,” said Head of the current board. “Why would you not just see what it’s all about?”

“It’s an apathetic attitude toward truth.”

The denied still work in public

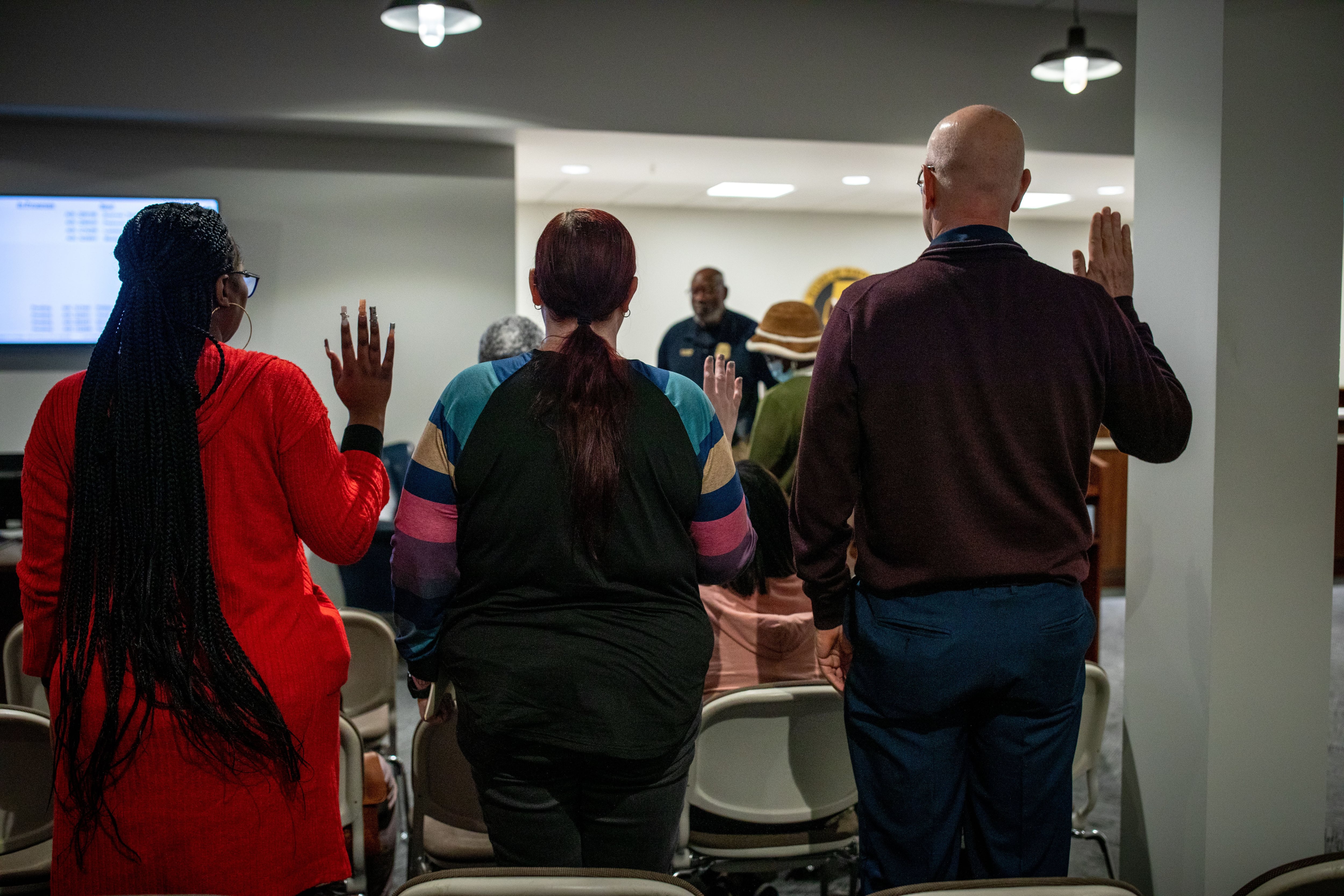

Wendy Pearson this month spoke to the parole board on behalf of her son, Eric Pearson, who is serving time for an armed robbery in Russell County.

Wendy, a disabled military veteran who served in Iraq, told the board that Eric had learned his lesson. He’s already been outside prison walls, on work release for five years, paying taxes and using the money left over — the state takes nearly half of work release inmates’ checks — to pay restitution.

Work release is the target of a new federal lawsuit alleging Alabama effectively runs a “labor-trafficking scheme” worth $450 million a year. The suit questions why inmates are deemed safe to work with the public in fast food restaurants and factories, but aren’t fit to be paroled.

“Labor coerced from Alabama’s disproportionately Black incarcerated population is the fuel that fires ADOC’s extremely lucrative profit-making engine,” reads the suit filed last month by former inmates and labor unions.

Last summer, over 86% of parole applicants who were assigned to work release facilities were denied parole, according to data gathered by the ACLU of Alabama over a 10-week window.

“They are already in the community,” said Alison Mollman, the legal director for the ACLU of Alabama. “They are vetted to work. Why can’t they go home to their family at night?”

“People are not being incentivized to do good things by this parole board,” said Mollman. “We should be showing people on the inside that if you do good things, you get parole.”

As for Eric Pearson, he took all the classes offered in the facilities where he’s been housed, his aunt said to the parole board. She described him as a kind-hearted man who had lost his way.

“What’s he good at?” asked board member Littleton.

Technology, architecture, welding and building, she replied.

But a representative from the Alabama Attorney General’s Office opposed Eric Pearson’s parole, citing prison infractions and the nature of the original crime.

Eric Pearson was lucky. He was paroled on Jan. 9 on a split vote. Gwathney alone voted against, seeking to push Pearson’s next hearing five years down the road. Simmons and Littleton voted to release him.

His mother raised her hands silently in thanks after the decision. It was the second time Eric has been up for parole. “This time I was praying that he was gonna get it,” said Wendy after the hearing. “There was no reason not to get it.”

She wasn’t surprised Gwathney voted against his release. “I think they hold up a certain criteria that one of them is going to vote no,” she said.

The case that changed everything

Two things happened around the same time Alabama decided not to let nearly anyone out of prison: The appointment of Gwathney as board chairperson and a triple murder by a man on parole.

First came Jimmy O’Neal Spencer.

Spencer sits on Alabama Death Row for killing two women and a 7-year-old in north Alabama while he was on parole. Spencer, who had a string of arrests beginning in 1984, was twice sentenced to life imprisonment, but he was granted parole in 2017 and released to a homeless shelter in Birmingham. He was supposed to remain there for six months, but he left three weeks later.

He went on a crime spree, but wasn’t picked up for violating parole. No one seems to know why he remained free, but everyone can agree he fell through the cracks.

On July 13, 2018, Martha Dell Reliford, 65, Marie Kitchens Martin, 74, and Martin’s great-grandson, Colton Ryan Lee, were killed after Spencer strangled and stabbed Martin before taking off with a wad of cash. Lee died from blunt force trauma.

Janette Grantham, the director of Victims of Crime and Leniency, at the time blamed the board’s dependence on risk assessment tools, “Paroles of violent offenders are being released by checkmarks on data driven parole guidelines. Two board members made a couple of check marks and here we are.”

Her group, VOCAL, attends Alabama parole hearings and opposes the release of many prisoners – primarily those convicted of violent crimes, she said.

No one from the victim’s group spoke against Spencer at the time. Grantham said it was because the board hadn’t included him on their list of violent offenders.

“By being reckless, three people got killed,” said Grantham of the parole board’s decision to release Spencer.

She added the current board is doing a good job, saying she wasn’t bothered by the plummeting parole rates.

“To me, the most important thing is we don’t have any new victims.”

The Gwathney Effect

After Spencer’s arrest came the appointment of Gwathney.

Following the triple-killing, Gov. Kay Ivey and Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall criticized the handling of the case and other parts of the parole agency’s work. State lawmakers in 2019 passed legislation that made some changes to the board, how it operated and how its members were appointed.

Head, who did not vote on Spencer’s release, resigned as head of the parole board in October of 2019. She said she left after changes gave the governor more control of the board.

“I felt like I no longer had a place there because I was interested in reducing recidivism,” said Head. “And there was nothing indicating that was going to happen.”

Ivey named Gwathney as her replacement.

Before then, Gwathney had worked as an assistant Alabama attorney general and in the Jefferson County District Attorney’s office. She worked on several high-profile cases during her tenure in both offices, including working on the Evan Miller appeal that had previously reached the U.S. Supreme Court. In that case, she argued against the possibility of parole for Miller, who had committed murder at 14.

Gwathney’s effect on the parole board was immediate.

The number of times she has granted parole wasn’t available from the bureau’s data department, because the bureau doesn’t keep electronic files of each board member’s voting record.

But according to data gathered by the ACLU over a 10-week period last year, the board heard 251 parole hearings in June and July of 2023. And in those, Gwathney voted to grant parole in just six cases — or 2.4% of the time.

During that same period, her fellow board members were more lenient. Littleton voted to grant parole in 8% of those cases. Kim Davidson, who temporarily sat on the board last summer, voted to grant parole in 12.4% of the cases.

That same data showed that someone from the Alabama Attorney General’s Office or VOCAL opposed parole in more than 78% of hearings. During that 10-week period, each time someone from the AG’s Office spoke in opposition, Gwathney – a former employee of the AG’s Office – voted no.

“We expected that she would oftentimes vote in line with the AG’s office…” said Mollman, the ACLU legal director. “We did not expect it to be 100 percent of the time.”

What does it take?

Antwan Lambert had a big name come to support him on Jan. 9. But even that didn’t sway Gwathney.

A full row of family members showed up to support the 32-year-old’s bid for freedom. His fiancée, who works in corrections, told the board how Lambert tutors her 6-year-old over the phone.

Lambert was sentenced to 20 years for a 2010 robbery in Mobile County.

In Alabama, a person’s initial parole consideration date is significantly less than the sentence. For most crimes, a prisoner is eligible for parole in 10 to 15 years or less. The longest someone will serve before being eligible is 15 years.

Lambert’s sister testified for him, too. But it wasn’t her voice before the board. She played a recorded message from Lambert on her iPhone. He talked about the mistakes he made when he was younger, how he’s grown up in prison and is working to be a better person. He also talked about the welding education he’s completed.

“It’s important for me to be a good role model for my nieces and nephews so they won’t have to go through what I’ve been through,” he said.

“At first, I can say I wasn’t ready. But now I know I am… I know a lot of folks might not see it that way, but I really am.”

Then, Bart Starr Jr. of the famous football family took the podium. He said Lambert has grown in prison and is committed to building a life and career.

Starr also talked generally about parole, telling the board they didn’t hear from enough ordinary people and that communities should help those who get a second shot. “We need to be part of his extended family,” he said during his two-minute speech, as the timer beeped.

An attorney general’s representative said the 20-year sentence, of which Lambert has served about 13 years, isn’t long enough.

Gwathney voted against his release. Unlike most, Lambert got lucky. The other two board members voted in his favor.

“I know I can’t right my wrongs overnight, but I’m trying,” said Lambert in his voice memo.

A life and death issue

Not everyone is critical of this parole board.

“I think they’re very effective,” said Grantham, the director of VOCAL. Her brother, Coffee County Sheriff C.F. “Neil” Grantham, was fatally gunned down outside the county jail in 1979.

Now, more than four decades later, Grantham leads the victim’s rights group.

“I think this board is doing good,” said Grantham. She’s witnessed many boards during her 15 years with VOCAL.

“I think they are very careful about the ones they release. I think they look at (the inmate’s) record and all the different tools in that toolbox and make, to me, the right decision.”

VOCAL primarily opposes parole for violent offenders, she said. Murders, sex offenses, or any crime involving a child is their top priority. A representative will attend a hearing to speak against release for someone convicted of a lesser crime, like burglary, robbery or drug crimes, if a family member requests their presence.

In an effort to examine parole nationwide, the Prison Policy Initiative analyzed data from 29 states. Most saw parole rates above 40% in 2022. That year, Alabama paroled just 10%, placing it dead last among all states surveyed. In 2023, the rate fell even lower in Alabama.

She thinks much of the scrutiny on the parole board is one-sided.

“A lot of people on the other side don’t consider the victims,” she said.

“Well, the victims didn’t choose to be there. They were just victims.”

“It’s not a bug, it’s a feature”

In 2019, lawmakers said the board should “clearly articulate its reasons for approval or denial of parole…”

Rep. Chris England said the purpose of that law was to inform an inmate on what they need to do as motivation to change their behavior. But the board has taken that to mean checking a box on a piece of paper with reasons as to why a person was denied.

Those reasons include lack of participation in rehabilitative programs, a negative institutional conduct record, the severity of offense being high, negative input from stakeholders (victims, victims’ families, law enforcement), prior parole violations, and more.

“I had to come to terms with something. I look at the system as it’s not working in my opinion,” England told AL.com.

He said an inmate’s prison record doesn’t seem to affect the parole board’s decision or how they use their discretion.

“It doesn’t matter if you’ve been a model citizen (in prison), it doesn’t matter if you’ve demonstrated for years that you’ve been rehabilitated even amongst some of the worst conditions in the world,” said England.

The board members have full discretion in their choices.

“With that discretion you have to own all those problems,” said England.

Lawmakers introduced a bill to create oversight for the parole board, but it died after Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall released a lengthy statement slamming it.

“Every inmate in the custody of the Alabama Department of Corrections was sentenced by a judge to a term of incarceration, but today, a sentence is hardly more than a suggestion,” he said at the time. He added that the board’s job is to “deny parole to those who present a threat to public safety.”

Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of Justice has for years said Alabama’s prisons are overcrowded and unsafe as a result, as Alabama fails to prevent violence and sexual abuse among inmates and fails to protect inmates from excessive force by prison staffers.

The federal trial is set to begin in November.

“Between good time, mandatory early release, education incentive time and the like, there is essentially nothing left to whittle away,” said Marshall. “Perhaps that is why the anti-incarceration crowd has set its sights on the Board of Pardons and Paroles – there is nobody else to ‘blame’ for our prison rates, least of all the criminals themselves.”

England has already introduced a bill for the next legislative session to create the Criminal Justice Policy Development Council to require the board follow its own guidelines.

Cam Ward doesn’t sit on the board or make decisions as to who gets let out, but he leads the agency that monitors everyone on parole and probation. He said changes are coming, and that inmates will soon have their voice heard at parole hearings.

“I have seen where many states have provided opportunities for inmates to speak before the board through a pre-recorded video and I believe that’s an avenue we should pursue for more transparency in the parole process,” he said.

People opposing parole would get the same opportunity to submit a video, he said.

The three parole board members serve six-year terms, and Gwathney’s term ends in 2025. There are no term limits, and the group who sends nominations to the governor could rename her.

But England does not expect rates to change under the current board.

“This isn’t about public safety,” said England about the staggering denial rate and the racial disparities. “This is not a coincidental trend… It’s not a bug, it’s a feature.”

This project was completed with the support of a grant from Columbia University’s Ira A. Lipman Center for Journalism and Civil and Human Rights in conjunction with Arnold Ventures.