Leon Hotchkiss, now 68, remains behind bars in Alabama, spending decades imprisoned for growing pot.

Authorities seized about five and half pounds of the plant on his property in Baldwin County, allowing authorities to charge him under the state’s marijuana trafficking law.

In 2013, Hotchkiss was sentenced to spend the next 40 years in prison.

And when he came up for parole in February, after serving a decade, the three-member Alabama parole board voted to keep him there.

The board set his next hearing in 2028 – the furthest they could push it back. He’ll be 73.

Today, Hotchkiss is incarcerated at the Loxley Community Work Center, although he spends most days outside the lockup. Each morning, he is dropped off at his job at a Fairhope boat dealership.

Jody Cullifer recently retired from the dealership, but he’s the person who secured the job for Hotchkiss. He said he had trouble finding a person to wash the boats, so he called the prison and asked if they had anyone who could do the job and provide general maintenance. They sent Hotchkiss.

On Hotchkiss’s first day, Cullifer explained the job. “He picked up really quick… and did a phenomenal job,” he said.

Cullifer called Hotchkiss a good worker and a trustworthy employee, and said the bosses gave him his own key to the dealership. That way, Hotchkiss could let himself inside in case the prison van dropped him off too early in the morning.

Now, Hotchkiss is responsible for handling the golf carts, general labor, maintenance and more.

“When I say hard worker, you couldn’t outwork him,” Cullifer said.

Hotchkiss — who goes by his middle name, Bud — was convicted under the state’s marijuana trafficking statute, which requires people with a certain amount of pot to be charged with trafficking, regardless of whether there is evidence of selling the drug.

That law provides several different levels of trafficking, and Hotchkiss was convicted under the lowest level – having between 2.2 lbs and 100lbs. That weight includes all parts of the plant, root and stem and all.

When asked about Hotchkiss’s charges, Cullifer scoffed and said the 68-year-old should “absolutely not” be imprisoned for four decades on marijuana charges.

He always cringed seeing Hotchkiss, who also has medical issues, board the prison van and return to the Loxley prison each night.

In recent years, as prohibition of marijuana has ended across much of the nation, the number of people prosecuted in Alabama for marijuana trafficking has also fallen off. According to the Alabama Sentencing Commission, there were just 13 trafficking convictions in fiscal year 2021, down from 16 in 2020 and 33 in 2019.

And the trafficking laws were most frequently used during those years to secure convictions for methamphetamines.

The parole denial came despite Cullifer’s best efforts. Cullifer, advocating for Hotchkiss, appealed to the local district attorney’s office and to his state representative. He started a social media campaign and other people spoke to the board on Hotchkiss’s behalf.

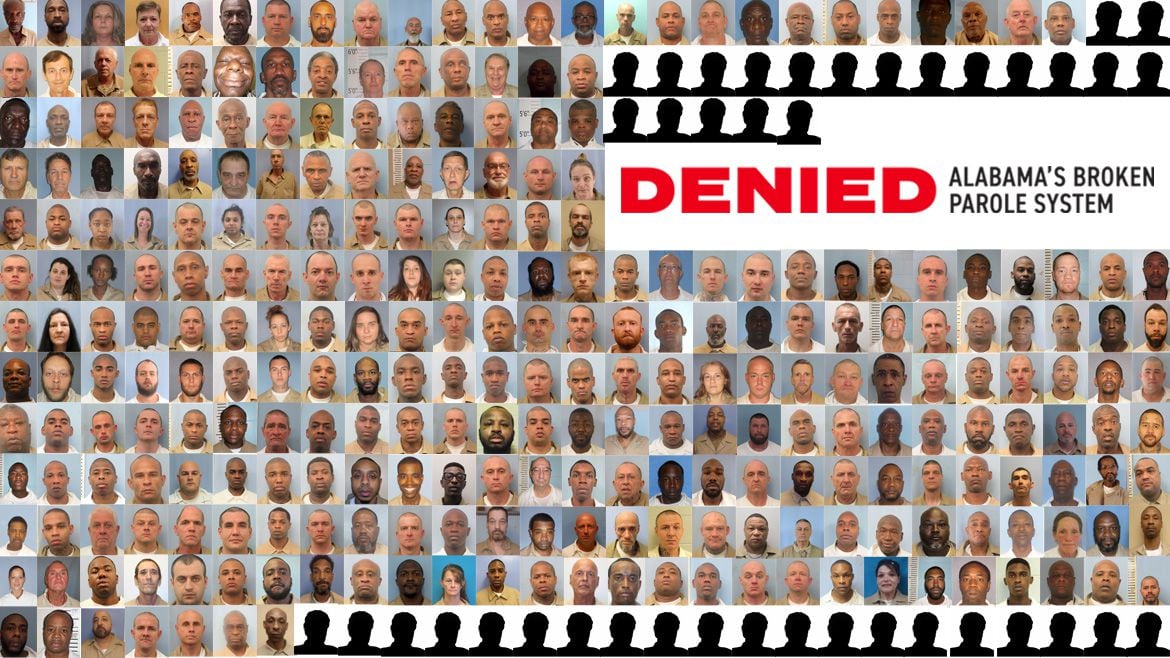

But the odds were always stacked against him. The current Alabama parole board now denies nearly everyone, despite a prison system that is in the federal crosshairs for being dangerously overcrowded. Fewer than one in 10 people who came before the board were granted parole in 2023 – only 8%.

That’s despite the board’s own guidelines showing most of those people, more than 80%, qualified to be paroled. That’s despite cases, like Hotchkiss’, where family or advocates appeal on behalf of an inmate.

“He’s not a danger to a soul,” said Cullifer. “He’s just a great guy. He really is. He needs to be in prison like I need to be in prison.”

In the end, the state still decided Hotchkiss, like so many others, was safe enough to work in public without supervision. But he still must spend his nights in the lockup.

Hotchkiss has no end in sight. If he serves his entire 40-year sentence in prison, he would be released at the age of 98.

“He’s serving a life sentence for growing marijuana… we’re playing politics with a man’s life.”

This project was completed with the support of a grant from Columbia University’s Ira A. Lipman Center for Journalism and Civil and Human Rights in conjunction with Arnold Ventures.