Alabama’s parole rate, which fell to a historic low last year, rose steadily during the first half of 2024 as the board gave a second chance to more non-violent offenders who had languished in the state’s dangerously overcrowded prisons.

“I’m delighted to know that, with balance, fairness and some modicum of consistency, our parole numbers are on the rise,” said Birmingham-area criminal defense lawyer Tommy Spina. “It’s been a long time coming.”

The parole rate during each month of 2024 has been more than double the average for 2023, peaking so far in February with nearly a quarter of parole applicants granted.

“Until recently, the parole board was exceptionally reluctant to grant parole under any circumstances to practically any individual,” said Spina.

Last year, the board released just 8% of eligible inmates. That’s despite the parole board’s own guidelines suggesting more than 80% of the prisoners should qualify for a second chance. The board even rejected all 10 people over 80 who were up for parole in 2023.

In January, as the board came under public scrutiny, that changed. The board granted 23% of those who had a parole hearing that month. In January of last year, the board let out almost no one — just 2% of cases were granted.

And the board has continued to grant more second chances. By February of this year, that number rose to 24%, according to data from the Bureau of Pardons and Paroles. In March, bureau data showed a slightly smaller parole rate of 18%. While the bureau hasn’t released its official April data, numbers analyzed by AL.com revealed a parole rate of 19% that month.

Numbers from May haven’t been released.

In addition to the rising parole rate this year, there have been additional requirements added to some inmates’ releases. Those conditions vary from required mental health assessments to completing counseling, to attending Alcoholics and Narcotics Anonymous meetings.

One person was paroled on the condition they apply to Southern Union Community College; another if they completed an HVAC training program.

Rep. Neil Rafferty, D-Birmingham, said he thought the board was moving in the right direction. The additional programming is helpful, he added, especially for those with substance abuse issues or mental health disorders.

“Adding those additional requirements is not going to hurt anything,” he said.

He also said services like the Perry County PREP center, a 90-day residential readjustment program that some people must complete before release, has also helped.

“I think there is still a lot that needs to happen to the board, but I think a lot of that progress can be credited to the bureau and what they’re doing in Perry County.”

Cam Ward, the former state senator who now leads the Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles, said more than 400 men have completed the PREP program in the three years since it opened. No one who has gone through the program has committed a new offense and gone back to prison, he said.

“I think the uptick you’ve seen in parole grant rates, you haven’t seen an increase in crime among those who are on parole. If the programming is in place, everyone feels confident it’s going to do some good. It all goes together and it works. The programming is working.”

Primarily, the board has been paroling people convicted of crimes that didn’t leave anyone physically injured or resulted in minor injuries. These people are paroled on what’s called a split vote, mostly with ‘yes’ votes by board members Darryl Littleton and Gabrelle Simmons and a ‘no’ vote by board chairperson Leigh Gwathney.

Public records don’t reflect the voting record of parole board members, and a spokesperson for the bureau has said the voting records are not recorded digitally. But from hearings AL.com has observed, while working throughout the year on Denied: Alabama’s Broken Parole System, the 2-1 split vote became common this year after the board came under public scrutiny.

The legislature

The board also got the attention of state lawmakers this year. They introduced five bills focusing on the parole board, its members and how they make their decisions.

All of the bills died.

But Rep. Chris England, D-Tuscaloosa, said he plans to reintroduce them next session. At the beginning of the last session, he said there was a “new motivation” in Montgomery to talk about Alabama’s unwillingness to let people out of overcrowded prisons.

The state’s prison system, as of April, houses 20,445 inmates in its facilities that are designed for 12,115. There’s construction ongoing for a more than billion-dollar facility in Elmore County, and plans for another one in the southern part of the state. The new buildings come as Alabama’s lockup system is being sued by the Department of Justice for unconstitutional, and unsafe, prison conditions.

“The system was never designed to have a parole board that didn’t let anyone out,” England told AL.com earlier this year.

Like Rafferty, his colleague in the legislature, England is encouraged about the rising rates. But, he doesn’t think that’s where the change ends.

“The system is still structurally broken and needs to be reformed,” England said. “Whether or not someone gets paroled should be based on things such as guidelines, evidence of rehabilitation and risk of reoffending, and recommendations of those that are intimately familiar with the applicant. It shouldn’t be subject to the whims of someone with an agenda.”

“So while the increase in grant rates is certainly a step in the right direction, long term comprehensive reform and oversight need to be implemented so that grant rates don’t rise and fall just based on the whims of the members of the board.”

Denied: Alabama's broken parole system

- Alabama lawmakers distance themselves from parole board, families say loved ones ‘stuck for life’

- Alabama argued to keep Lowe’s shoplifter in prison. Roy Moore came to his defense.

- He missed a meeting and got sent back to prison. Now Alabama is giving him another chance.

- They want to ‘die with a clear conscience.’ But in Alabama, pardons are harder to come by

- Battered woman shot her abuser 32 years ago. Alabama’s parole board won’t let her out.

Rafferty said the board needs more oversight, and outcomes shouldn’t drastically change based on who is sitting in one of the three board seats.

“The board is an institution, not a person. And it should be treated and regulated as such.”

Other groups speak out

Groups like the ACLU of Alabama supported some of those legislative bills that died, including the bill to allow inmates to appear virtually at their parole hearings and a reform bill that had measures for sick and elderly inmates. Representatives from the ACLU have been keeping detailed data from parole board meetings each week and releasing them in reports, like the one they published last year.

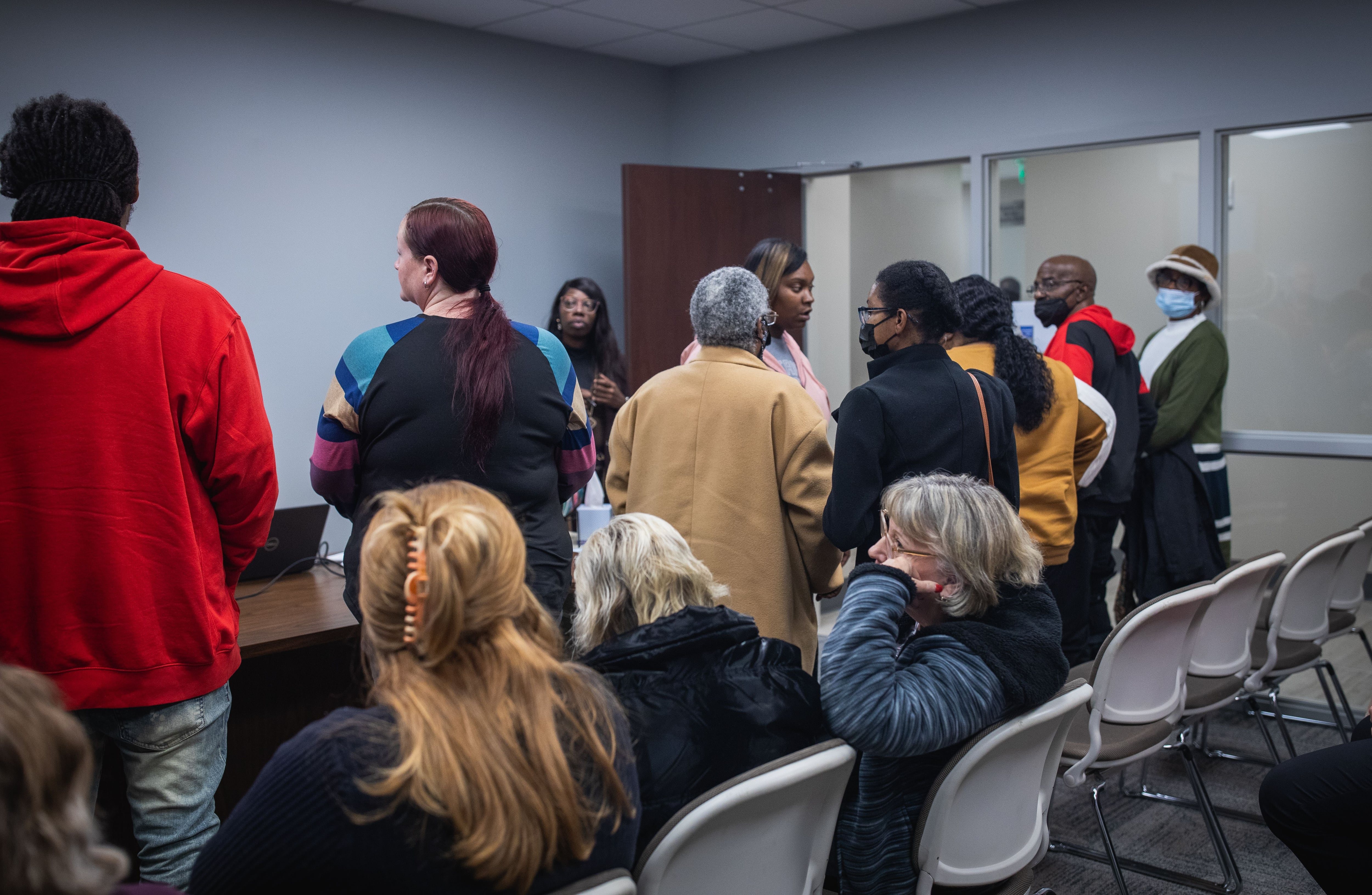

During its Alabamians for Fair Justice Lobby Day, about 60 people visited the Alabama State House to talk to lawmakers about the parole board and legislation.

Also in April, the Public Affairs Research Council of Alabama hosted an event focused on the Alabama prison system and legislation surrounding the state’s criminal justice system, but most of the audience used the question-and-answer period to ask panelists about Alabama’s parole board and how changes could be made.

Contentious hearings

The increased public scrutiny and AL.com’s continued reporting on the lack of paroles accompanied an increase in split votes and strained meetings at what had been brief board hearings.

During one contentious hearing in April, board chairperson Leigh Gwathney, who votes ‘no’ more than her colleagues, questioned the motives of a woman who said she forgave her daughter’s killer. Gwathney also called out AL.com for its reporting of the board.

“It’s often times reported that that’s what we do — that we show up and we make a very quick, two-second decision. And that is the furthest from the truth,” Gwathney said.

“What happens is that each one of us spends more time than anybody could ever imagine studying these files, backwards and forwards from cover to cover before anybody ever shows up. And you couldn’t begin to know what all is studied because our files are privileged, despite how hard some people try to get our files.”

Gwathney said that members of the media only see the people who attend parole hearings to support or protest, and can’t know who has written letters to the board and voiced their position.

“Well a lot of times people don’t show up because they can’t afford to leave their jobs. Or they can’t afford to have somebody watch their children. Or they might not, you know, might not be comfortable... Well, I bet AL.com can imagine that it’s a tough world out there, right?”

AL.com spent months reporting on the board and profiling a dozen of the denials — parole denied for a man already let out to serve fast food near the beach, or for a man serving decades for growing marijuana, or for a woman who shot her attacker.

Gwathney has declined to comment for those stories. But, in April at a public parole hearing, she directly addressed AL.com. “Y’all started having somebody come more often and I’m glad for that. And I hope that y’all remember that it’s tough for folks to come to these hearings. It really is.”

A former prosecutor in Jefferson County, Gwathney most recently worked in the office of the Alabama Attorney General, which sends someone to oppose most parole applications.

Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall, the state’s top prosecutor, last year wrote a column declaring that the state’s overcrowded prisons only housed dangerous offenders and “there is simply nobody else to ‘reform.’”

But he also hasn’t said much in public about paroles this year.

When AL.com asked in March if he still stood by that position, a spokesperson responded via email: “We do not have anything further to add, as we disagree with the premise of every article you have written on the topic.”

This project was completed with the support of a grant from Columbia University’s Ira A. Lipman Center for Journalism and Civil and Human Rights in conjunction with Arnold Ventures.