On a spring day last year, the Alabama parole board split over the fate of Fredrick Bishop. They voted 2-1 to send him back to prison. But the board members missed a key detail in the case.

The man was already dead.

Bishop, who was 55 and from Lineville, was serving 20 years in prison for a 2008 robbery conviction.

“Fredrick was a good boy,” his mother, Dorothy Jean Bishop, told AL.com last year.

He came up for parole in March of 2023, and two out of the three members at the time denied his release.

But Bishop had died 10 days earlier. He was incarcerated at Easterling Correctional Facility in Barbour County, and that’s where he was found unresponsive. Prison officials said he was taken to the prison’s healthcare unit and later died. The cause of death hasn’t been released.

He wasn’t actually set to appear in front of the board, anyway. Prisoners in Alabama don’t get to attend parole hearings where the board decides their fate in just minutes.

In fact, Bishop’s not the only prisoner to be ordered back to prison despite already being dead.

Hearings are brief. Many prisoners lack representation, so no lawyer or family member even shows up to the hearing in downtown Montgomery. Those who do show up get just two minutes to speak. An inmate is reduced to pieces of paper, a list of check marks to grade their disciplinary record, severity of past offense, time served, and other factors.

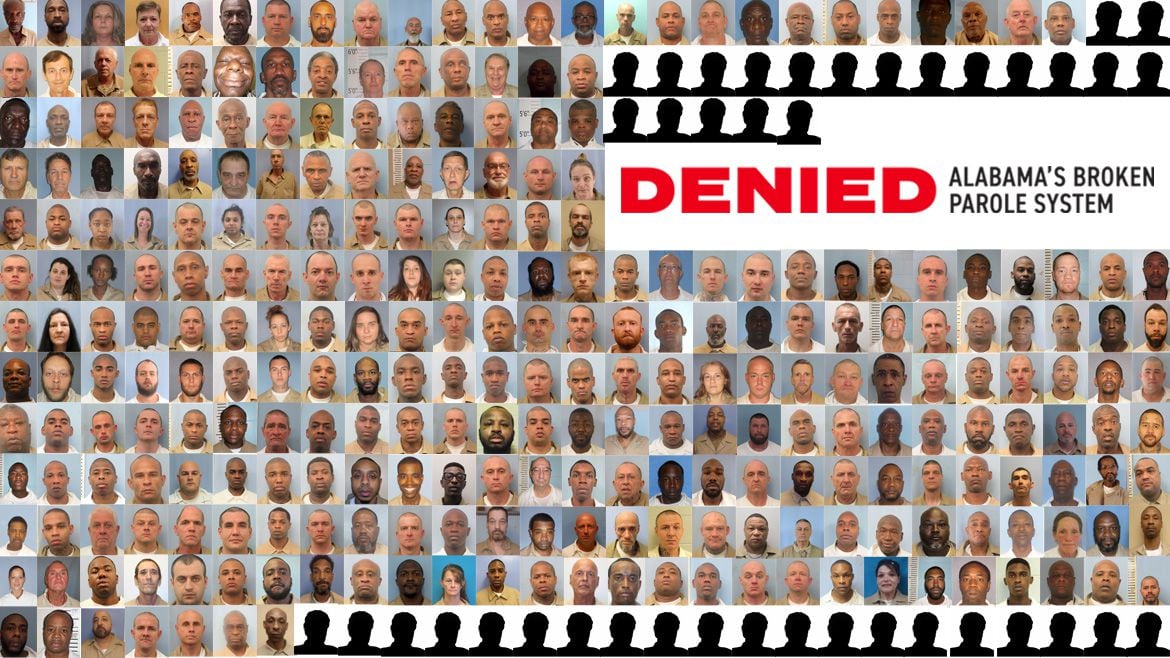

And in 2023, the parole board looked at those forms and rejected nearly all of them, blocking release of all but 8% of the prisoners.

That’s despite the board’s own criteria showing about 80 percent who came up for parole were recommended to be released. That’s despite a prison system at 168% capacity, a system so dangerously overcrowded it’s being sued by the Department of Justice for unconstitutional conditions.

Bishop’s mother, Dorothy Jean Bishop, said what happened to her son was incomprehensible.

“I can’t believe that,” said the 79-year-old. “But I believe it, because they don’t care.”

Fredrick Bishop died on Feb. 27, 2023. His parole hearing was on March 9.

Denied: Alabama's broken parole system

- Alabama lawmakers distance themselves from parole board, families say loved ones ‘stuck for life’

- Alabama argued to keep Lowe’s shoplifter in prison. Roy Moore came to his defense.

- Alabama paroles hit historic lows last year: Here’s what changed amid scrutiny in 2024

- He missed a meeting and got sent back to prison. Now Alabama is giving him another chance.

- They want to ‘die with a clear conscience.’ But in Alabama, pardons are harder to come by

After members of the media called out the error, the Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles communications director sent a statement: “Typically, inmates who are deceased are removed from the parole hearing docket; however, the Board was not aware at the time of the hearing that Bishop had recently passed away. "

“The Bureau apologizes for any confusion this may have caused interested parties and will continue to take steps to avoid this and similar situations in the future.”

Dorothy Jean Bishop sighed while talking to AL.com. “They don’t care about regular people.”

The day her son came up for parole, the board heard 22 cases. They granted just one.

In Alabama prisons, hundreds of people die each year. According to the latest available report from the prison system, which had numbers through September 2023, 337 death investigations had been opened during the fiscal year.

Brandon Clay Dotson met a similar fate as Fredrick Bishop. Dotson, 43, was found dead at Ventress Correctional Facility on November 16 – the same day as his parole hearing.

He, too, was denied.

Dotson died in prison, and his body was eventually returned to his family following an autopsy at the Alabama Department of Forensic Sciences. His family later discovered he had been returned without a heart.

There’s no clear data on how many inmates have a parole hearing after they die behind bars.

“What can be done about it?” asked Dorothy Jean Bishop. “Nothing?”

She said her son had a lot of friends. She said he was a really good athlete, and he was. Records show he was an all-state linebacker for 3A Lineville High School in 1984.

He often wrote and called his mom. She had planned a trip down to see him, but he died before they got there. Had he been paroled earlier, she said, maybe he would have gotten to see his mom again.

“Some of them are not even human beings,” said Dorothy Jean Bishop of the board. “The people that are doing it are not human.”

This project was completed with the support of a grant from Columbia University’s Ira A. Lipman Center for Journalism and Civil and Human Rights in conjunction with Arnold Ventures.